Editorial nudity is a part of pop culture. So why does the internet think it's porn?

The presence of nudity and promiscuity in music, fashion and art is an unquestioned truism within society. So why do we assume the intention is pornographic when it comes to new media?

One of the most exciting and invigorating parts of popular culture over the course of modern history has been the use of the human body as a medium through which to express its ideas. Whether those are about sexual empowerment, civil rights abuses, or commentary on the behaviour of the media, the human body has been used as a canvas to complement the messages of music and fashion for thousands of artists.

At various points, the level of promiscuity used has been considered unacceptable, controversial and game-changing, with figures like Marilyn Monroe, Madonna and Lady Gaga as nodes on the ever-growing tree of cultural expectation. In all forms of media, the ubiquity of nudity has only grown: its presence in film, its presence in fashion, and its presence in music as something of a holy trinity of examples.

These days, the use of nudity is so common that its employment isn’t typically questioned. While artists continue to find new ways to create shocking imagery with it (see Lady Gaga’s 2009 VMAs performance, or even Ice Spice’s infamous signature twerk), seeing a celebrity in visual imagery either naked, lewd, or sexually implicit, is not considered abnormal by the masses. The consensus from within the industry is firm: nudity is editorial.

The wonderful thing about editorialising the human body is that it becomes a tool for telling so many stories and exploring so many ideas. If those ideas are explicitly sexual, then so be it. The existence of sexuality is no less qualified to be considered art; it is an innate human trait which drives the conquest of humanity within this moribund world. Sexuality has been the target of oppression as well as the tipping point of power. Monarchies who persisted through their - to put bluntly - horniness, leading to the world we live in today. Human beings systemically murdered for the forms of their own sexual preferences. The stories people want to tell through their music and their bodies and their photography and their art can understandably be explicit. And, to put simply: sex is fun. Sometimes people just want to yell about this thing they enjoy.

However, what art is not, is porn. Porn and editorial art are two separate things with two separate purposes. That is not to say pornographic material cannot be artful, nor is it to say that editorial art cannot be arousing. But the primary delineation between them both is their intention. With porn, the primary aim is to give the consumer a product that is arousing, and potentially leads to their self-pleasure. With editorial, the aim is to tell a story through art. When an individual or team sets out to create one or the other, they do so with a specific aim in mind.

This aim is typically understood by large parts of the populace. When a fashion model posts a photo in an underwear set or bikini, it’s largely understood that the purpose of that photo isn’t to be pornographic material. Their body is acting as a canvas for a garment. When a pop star dances on our screens in a skimpy outfit, we don’t typically mistake it for porn - we just know that this is a thing that pop stars do as part of their holistic performance.

Of course, this isn’t always true. In 2022, Killer Mike came to the defence of Meek Mill on Twitter, whose Expensive Pain album art received criticism from Philadelphia locals incensed about its advertisement around their city. He tweeted, ‘It's art. Absolutely. We as a society see naked humans in art in museums. We should also be cultured enough as adults & parents to have a convo about nudity & art with our children. I say this as a parent, rapper & a High Museum of ART Board member.’ In 2013, when Miley Cyrus’ Wrecking Ball music video released, her nudity in the video caused vociferous controversy, which even went so far as to incite direct criticism from Sinéad O’Connor, whose Nothing Compares To You music video had directly inspired Cyrus.

In O’Connor’s open letter, she wrote, ‘I am extremely concerned for you that those around you have led you to believe, or encouraged you in your own belief, that it is in any way ‘cool’ to be naked and licking sledgehammers in your videos. It is in fact the case that you will obscure your talent by allowing yourself to be pimped, whether its the music business or yourself doing the pimping.’ Later on in 2023, as reported by Pitchfork, Cyrus went on to elaborate on the pain she felt being put down by another woman, and the implication that her creative decisions were goaded by men and not advised by her own choices.

All things considered, the general understanding and acceptance of nudity and sexual themes in popular media is at an all-time high. So why, then, is the digital media landscape not the same?

The world of digital and new media has been growing steadily since the turn of the millennium, a period of time during which we have evolved from niche Geocities websites, through MySpace bedroom producers, all the way to massive media empires that exist purely online. Content is wholly democratised, with anyone possessing the keys to celebrity if they want it. As trust in traditional media has continued to wane, the millions of listeners (and millions of dollars) attached to independent podcasters and online reporters have only grown. Mega pop stars like Justin Bieber and Troye Sivan burst onto the scene via Youtube, and short-form creators such as Addison Rae and Alix Earle have built empires through a free app. Anyone who wants to be an artist can be, and anyone who wants to be a porn star can be.

So why can the internet not tell the difference?

There are some caveats to this accusation. Certain pockets of the internet experience immunity from this kind of problem. Female influencers whose audiences predominantly comprise women tend to find their skimpy bikini selfies and Lounge Underwear sponsorships are perceived as cool displays of fashion taste as opposed to content created for sex. Areas of the internet unambiguously celebrating Art™ also find nudity more acceptable. But flying down the freeway of the mainstream online landscape and you tend to find that even small exhibitions of sexual imagery are labelled as pornographic.

It’s no secret that the rise of homemade sex content has been occurring online. With websites like OnlyFans allowing creators to run independent businesses providing anything from innocuous foot photos to full-blown porn, without having to deal with the unethical injustices of the porn industry itself, it’s been a go-to career for many. Particularly at a time where the job market is struggling, and people resent the authoritarian control corporations tend to have on their lives. When the top of the top flaunt their multi-million dollar earnings, the appeal can be hard to resist.

There is a large cross-pollination between the world of sites like OnlyFans, and the world of gaming. Video games have always utilised sexual imagery as part of its art form - anything from the classic triangle tits of Lara Croft, to the booth babe marketing strategies of the mid-2000s, to the gacha and MOBA games of today, whose female characters’ jiggling assets oftentimes experience a little more fluid dynamics than needed. As a result, the cosplay community has always had a faction that spills into these sexual themes, spawning new media celebrities like Jessica Nigri and Yaya Han. Sites like Twitch have faced vast controversy for their fluffy boundaries on mature content, with OnlyFans titan Amouranth pioneering the infamous ‘hot tub meta’ to funnel the male gamer demographic into her OnlyFans business.

Some have argued that the existence of these kinds of sites directly encourage men online to believe in their ability to buy sex from anyone, or that any content online which features a traditionally sexual part of the human body exists for the purpose of sexual gratification, as opposed to editorial. But that theory fails to take into account the time before these kinds of sites were so ubiquitous. While OnlyFans has been a massive talking point within the last few years, this is not an issue that has materialised in this decade alone.

The likely truth is hidden in the nature of the social media era itself: the intimacy of it. When a person - be they a stranger or not - posts content on social media that involves interaction with others, the content begins to feel personal. That content is not simply an expulsion into the void, but rather a tailored decision intended to make you feel something. When we are used to content being there for our consumption, it becomes easy to believe that every aspect is for personal enjoyment.

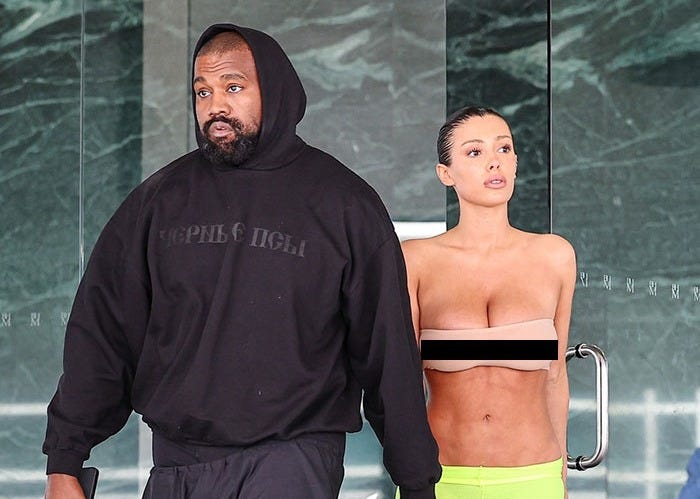

When we witness musicians and models engage in editorial nudity, we do so from a removed position. Either we see them through a screen, or from a crowd, or simply stamped as an image on an advertising billboard or an album cover in a store. If we were to raise our proverbial hand to reach out to them, we would find proximity limited by a glass wall between us. In essence, there is a level of inaccessibility that separates us from the artists, and that inaccessibility is what forms the justification, in our heads, for their otherwise promiscuous or uncouth behaviour. This is the same argument that has been made to explain why someone like Bianca Censori can be photographed in public wearing next to nothing, while your average private citizen would be arrested for public indecency.

Much like how art in a gallery is forbidden from touch, locked away behind red rope and glass protection, the celebrities who use editorial nudity as part of their art are given a pass because they, too, are inaccessible. When the selling point of new media is the accessibility and personal interactions between fan and figure, those actions feel less separate and less artful. If a woman’s breasts are visible, it’s because she’s trying to win the sexual attraction of each follower. If she wears tight clothes, or short skirts, it can’t be related to her own expression, her own story and her own fulfilment - because I’m right here, able to interact with her, and so it must be for me.

The irony in this kind of perspective is that the kinds of outfits you see hundreds of times on the street every day and think nothing of, can be seen as succubus traps online, worthy of criticism or accusation or discrediting. But once again: the strangers on the street wearing low cut shirts and short skirts and bikinis are strangers. We don’t question the fact they’re not for us. We can’t touch them or access their lives on a whim. So we don’t question the placement of their clothing choices or self-expression as anything but an expected part of society.

Editorial nudity and promiscuity are an integral part of many art forms. They have the power to tell important stories and empower people through their work. It can look beautiful without being sexual, or it can be decidedly sexual in theme. Whatever it is, it is normal and acceptable. When the people we see online engage in that kind of work, whether through photography, music, dance, or anything else, its intention should be assumed artful unless explicitly stated otherwise. When a person becomes known for their accessibility, or their normalcy, or in someway decidedly antithetical to the impunity of celebrity, they should not be subject to separate rules. If someone’s work, whether through vlogging, tweeting, streaming, or something else, makes them overtly relatable, they should not be held to different standards when they eventually decide to step into more abstract, artistic roles.

As an artist whose background is in new media, I have witnessed this phenomenon first-hand. Fans from my previous communities accusing me of turning to porn when I produce visual, fashion-focused art that barely scratches the extremeness that we accept, unquestioning, from celebrities. I have repeatedly asked myself what discredits new media figures from engaging in this widespread artform, and what we can do about it.

Ultimately culture and its expectations move with its own tides. Progress gets made, but only when the world is ready for it. The internet may be a melting pot of uncapped creativity and ideas, but it’s still called new for a reason. And people still place a folly between the ‘legitimate’ traditional media artists, and the ‘illegitimate’ digital media aspirants, whose imagery can be nothing but a soft launch of a burgeoning OnlyFans career. All we can do is keep making our art, and persist with the stories we continue to tell with our bodies.